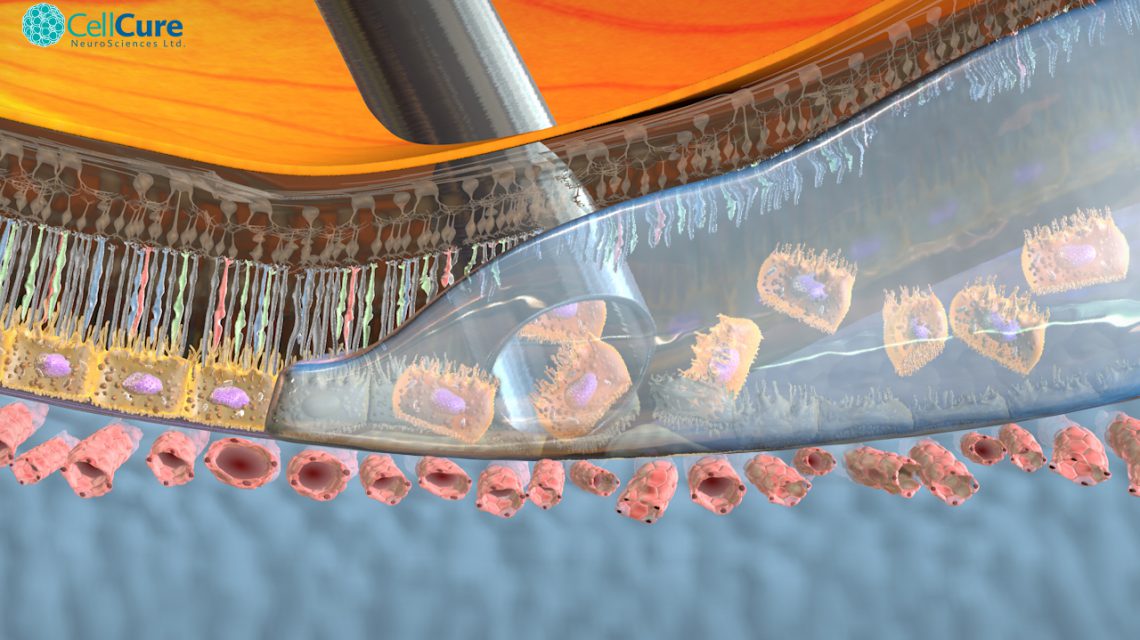

Pictured above: Stem Cell Transplant: delivery of hESC-derived RPE cells into the sub-retinal space, through a thin cannule.

Marking a successful start to the Hadassah Medical Center’s Phase I/IIa clinical trial, using a unique human embryonic stem cell therapy to stop progression of the dry form of Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD), the clinical trial’s Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) has endorsed the safety of the protocol and given approval to begin treating the next cohort of patients.

The DSMB is composed of an international group of medical experts that closely monitors the clinical trial. The stem cell product, called OpRegen®, is being developed by Cell Cure Neurosciences, a subsidiary of BioTime Inc. (NYSE MKT and TASE: BTX), jointly with Key Developers Prof. Eyal Banin, Director of Hadassah’s Center for Retinal and Macular Degenerations and a leading investigator for this trial, and Prof. Benjamin Reubinoff, head of Hadassah’s Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research Center and Chief Scientific Officer of Cell Cure. OpRegen® is comprised of retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells, which underlie and support the light-detecting photoreceptor cells that are so critical to vision.

The Hadassah “home-grown” stem cell protocol is unique in two ways: it uses only animal free (xeno-free) products in deriving and growing pure RPE cells from human embryonic stem cells (hESCs); and it grows those cells through a process called direct differentiation. Rather than let the stem cells grow and differentiate (develop) spontaneously in-vitro and then transfer the best cells to another dish to continue differentiating, the Hadassah team directs the differentiation process by adding factors that will guide the cells to become RPE cells. The potential danger in using spontaneous differentiation, Prof. Banin notes, is that the stem cells may turn into other types of cells, which could prove harmful if injected into the retina.

Dry-AMD is the leading cause of blindness in people over the age of 60, and a condition for which there is currently no FDA-approved therapy. In dry-AMD, there is a loss or dysfunction of the layer of RPE cells generally in the region of the eye called the macula, which is the part of the retina responsible for sharp, central vision that is important for facial recognition, reading, and driving.

The first cohort of three legally blind patients, two women and one man, received a low dose of 50,000 stem cells. Now Hadassah is authorized to move forward with the enrollment of the second cohort in the OpRegen® clinical trial. Recruitment will begin immediately. These patients will receive a higher, more clinically significant dose of 200,000 cells of OpRegen®. If that dose proves safe, a third cohort will receive an escalated dose of 500,000 cells. Enrollment in the second cohort is expected to be completed in 2016 and, if the data are positive, it is anticipated that there will be DSMB approval to proceed to the third cohort by the end of 2016.

The fourth cohort, which will consist of six patients, will be given the maximum dose. This fourth cohort will comprise patients who have slightly better vision, reports Prof. Banin. It is anticipated that these supportive cells will stop degeneration of the patients’ photoreceptors so they can retain the vision they currently have.

At this point, seven months have gone by since the first patient received treatment, with no adverse effects–such as retinal detachment, formation of a tumor or inflammation.

In addition, preclinical data have demonstrated that OpRegen® preserved vision and retinal structure when it was transplanted into the leading rodent model of retinal disease caused by RPE dysfunction. In addition, by injecting the hESC-derived RPE cells into the eyes of several pigs, the Hadassah team was able to perfect the subretinal delivery of the cells. Further, post-mortem histology revealed that the transplanted cells survived under the retina and maintained expression of proteins that characterize native RPE.

As Prof. Banin explains, an open question is that of possible immune response of the host to the transplanted cells. In the patients treated thus far, there has been no obvious inflammation, but chronic rejection cannot be ruled out. Prof. Banin emphasizes that the goal of the RPE stem cell treatment is to prevent further damage. After about a year, the researchers will be able to analyze whether there has been a significant progression of atrophy in the retina or whether the treatment has, indeed, slowed or stopped its progression. For greater objectivity, the analysis is done by a Data Reading Center and is a “masked” reading, which means the investigator does not know whether the data is from an eye that has been treated or not.

While this treatment is not able to generate new photoreceptors, which would be needed to achieve improved vision, Hadassah is, however, conducting preclinical research using stem cells to grow new photoreceptors. To date, Prof. Banin and Prof. Reubinof’s team has been able to create early photoreceptors, but they are not yet at the point of actually regenerating complete photoreceptors.

“The field is highly active now,” comments Prof. Banin. While Hadassah was the second research team to implant human embryonic stem cell-derived RPE cells to treat dry macular degeneration, there are now at least four or five other groups around the world, working with different methodologies. Hadassah, however, remains a world leader, using its unique protocol of xeno-free product and directed differentiation.

Adi Mohanty, Co-Chief Executive Officer of BioTime, notes: “The escalation of dosing in this Phase I/IIa trial is a significant achievement for our OpRegen® cell therapy program, and we will now begin to evaluate the higher cell doses that we believe will have the most likely potential and favorable outcomes to benefit the patient.”