For the past 20 years, patient David Levy*, 62, has suffered from a neurological disease that weakened his muscles. One of his vocal cords was paralyzed. He can only speak with the help of a hand-held voice amplifier. Recently, he suffered a heart attack, and the catheterization revealed serious heart blockages.

But at the meeting of Hadassah Hospital’s heart team—cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons—the experts were unsure how to proceed.

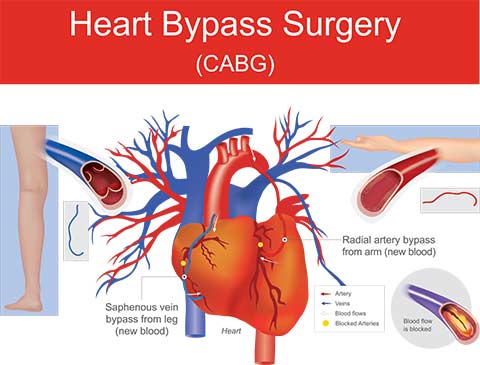

Ideally, Levy would undergo a triple bypass. But such an operation can take as long as four hours and would require intubation, which might damage the patient’s remaining vocal cord. It would also require neuromuscular blocking agents, or muscle relaxants, often used in surgery to prevent muscles from moving when a patient is unconscious.

Or they could go another way: partially repairing the heart in the cath lab. That would avoid problems with anesthesia but would give the patient only incomplete relief.

“We presented the patient with the choice,” said Dr. Alexander Lipey, a senior cardiothoracic surgeon. “From our point of view, 62 is young for a heart patient.”

Levy, who was still working and leading an active life, opted for the surgery despite the risks.

The cardiothoracic surgeons, wanting to reduce the risks, met with the anesthesiologists. Dr. Yuval Meroz offered a unique proposal.

Instead of intubating the patient, he would use a laryngeal mask, a medical device that keeps a patient’s airway open during anesthesia or unconsciousness.

“Such devices are used for hernia surgeries or ingrown toenails, not for heart surgery,” said Dr. Lipey.

Dr. Meroz explained that he would personally anesthetize the patient and that he wouldn’t make use of muscle relaxants.

“This meant constant involvement by Dr. Meroz, as we had to move the patient’s position, or when the patient made slight movements that required more anesthesia. We’re used to having a patient lying flat and being totally unconscious as we shut off the heart, attach the patient to a heart-lung machine, do the bypass, and then restart the heart,” said Dr. Lipey. “Dr. Meroz had to change the position of the laryngeal mask at least three times while we were operating. Even the slightest miss would prevent air from reaching his brain and cause brain damage. In my 20 years of surgery, I had never seen anything like it.”

Dr. Meroz, the staff reported, showed no stress during the complex procedure.

The triple bypass was a success. Levy had no neurological damage from the surgery, and his heart is beating fine. He’s already back at work.

*Name changed