Hadassah has been working on reducing the incidence of tuberculosis for nearly 100 years.

Nathan Straus, the founder and owner of Macy’s Department stores, believed that pasteurizing milk would help eliminate TB. To that end he supplied pasteurized milk to young children in 36 American cities. He then approached Hadassah to do the same in the Jewish settlements of pre-state Israel in the post-World War I period.

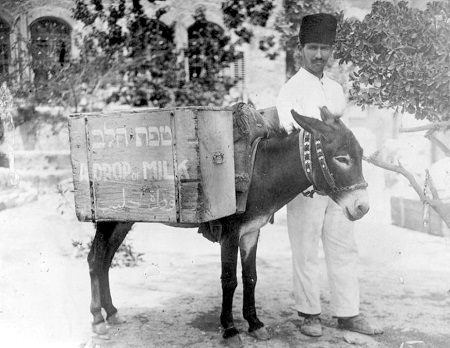

After arriving in Palestine in 1921, Bertha Landsman, an American nurse, opened Hadassah’s first permanent infant welfare station, Tipat Halav (drop of milk), in Jerusalem. The clinic offered care for mothers with newborns and made pasteurized milk available to needy families. Its overwhelming success inspired Hadassah to expand the program by delivering fresh pasteurized milk by “donkey express.” The program resulted in a marked reduction of the incidence of tuberculosis in the population by 1930, and the clinics themselves laid the groundwork for Hadassah’s efforts building the health-care system in pre-state Israel.

In 1926, Hadassah opened pre-state Israel’s first tuberculosis ward in its Safed hospital, which became the region’s tuberculosis center in 1935. The hospital was devolved to the Israeli government in 1957.

Today, TB is still being dealt with in Israel. “Despite the belief by many in the West that tuberculosis is a disease of the past,” reports Prof. Allon Moses, director of the Department of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases at Hadassah Medical Organization, “it has always been in Israel and has never gone away totally. When a case is diagnosed, the patients are sent to special isolation wards supervised by the Ministry of Health and are not treated at Hadassah’s hospitals.”

The good news is that it is as rare in Israel as it is in most Western countries. Of the 2,000 tests conducted in Hadassah’s specialized TB laboratory, only 10 to 20 cases of the disease are found. Most of those infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, an airborne organism spread by coughing, are immigrants from areas where TB is endemic.

TB disease shouldn’t be confused with latent TB, according to Prof. Moses. Men and women with latent TB—at least a third of the world’s population—do not have symptoms and cannot transmit the disease unless they transition to TB disease because of an HIV infection or malnutrition.