Scientists at the Hadassah Medical Center and Hebrew University have discovered a genetic mutation that is responsible for lack of ovary development. To date, very few genes have been identified that are important to ovarian formation and fertility and little is known about the processes involved in the development of the ovary or egg.

The discovery, which is expected to enable doctors to diagnose a cause of infertility and the absence of puberty, is a collaborative effort of Prof. David Zangen, head of Pediatric Endocrinology at Hadassah Hospital-Mount Scopus; Dr. Offer Gerlitz (Ph.D), Dept. of Developmental Biology and Cancer Research of the Hebrew University Faculty of Medicine’s Institute for Medical Research Israel-Canada; and Prof. Ephrat Levy-Lahad, Professor of Internal Medicine and Medical Genetics at Hebrew University and Director of the Medical Genetics Institute at Shaare Zedek Hospital in Jerusalem. The research is highlighted as the cover story in the November issue of the prestigious Journal of Clinical Investigation.

The mammalian ovary functions not only as the reproductive organ that contains the germ cells (oocytes) responsible for creating the next generation, but also as a hormonal gonad (reproductive gland) which regulates many aspects of female physiology and development. The researchers discovered a consanguineous family (descended from a common ancestor) where four female cousins presented with ovarian dysgenesis (a lack of ovarian development), despite the fact that each possesses two X chromosomes, as does a normal woman. Because these girls lacked sex hormones, they did not undergo the regular process of puberty. Rather, they were treated with replacement hormones, which allowed them to reach a normal height and to experience a monthly menstrual cycle.

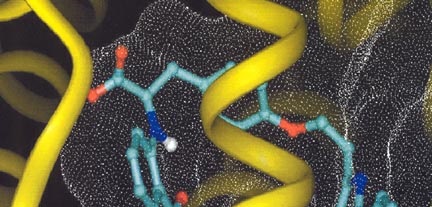

When the researchers mapped the girls’ genomes and searched for regions of genetic commonality among them which were not shared by their healthy relatives, they identified a mutation in the gene, Nucleoporin 107 (Nup107). The researchers then searched for a model that would provide experimental proof that linked this mutation to the lack of ovarian development. They found their model in the fruit fly—Drosophila, generating flies with the mutation that was identical to the one found in the affected girls.

Many of the female flies, the study team found, demonstrated significant impairment in ovarian development. The remaining mutant female flies did lay eggs, but minimally, and the majority of the eggs were deformed to the point that they did not hatch and lead to reproduction.

Consequently, the model proved the involvement of the Nup107 gene mutation in ovarian dysgenesis. The laboratories of Profs. Zangen and Levy-Lahad identified the consanguineous family with ovarian dysgenesis and discovered the mutation and gene, while the laboratory of Dr. Gerlitz generated the disease’s model in Drosophila.

“These results,” the authors explain, “indicate a pivotal role for NUP107 in ovarian development and suggest that nucleoporin defects may play a role in milder and more common conditions such as premature ovarian failure.”

The collaborative study was supported by grants from the United States Agency for International Development program for Middle East Regional Cooperation and the Israel Science Foundation.