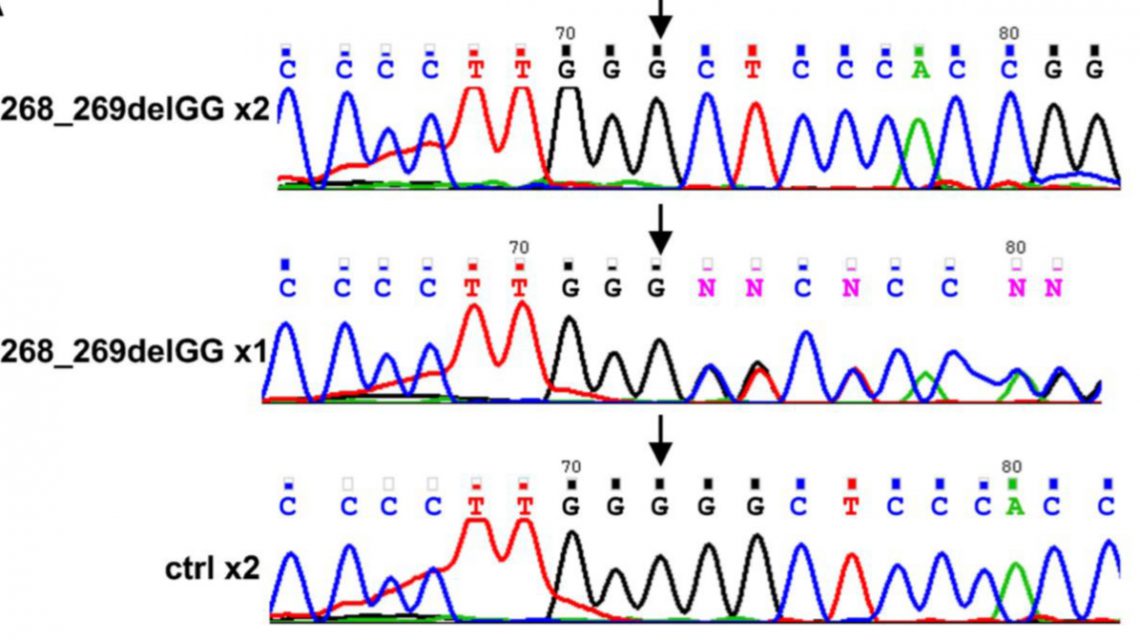

Molecular characterization of LAT mutation: Top=Patient; Middle=Parent; Bottom-=Unrelated healthy individual

The mystery of yet another genetic mutation that has fatal consequences for children has been unraveled by a tripartite collaboration initiated by the Hadassah Medical Center with colleagues from the Rambam Medical Center’s Ruth Rappaport Children’s hospital in Haifa and German partners. The cooperative venture is dedicated to the discovery and characterization of congenital diseases of the immune system.

Recently, successful collaboration led to saving 15 Russian children who suffered from osteopetrosis and a Palestinian child who had Evans Syndrome through bone marrow transplantation performed at Hadassah by Dr. Polina Stepensky, head of the Pediatric Bone Marrow Transplantation Unit.

The discovery of this new gene, called a LAT signaling pathology, is the first report of an LAT-related disease in humans. (LAT dysfunction had previously been defined in mice.) LAT, the Linker that is needed for Activation of T cells, is a critical signaling hub for a healthy, well-regulated immune system.

A child with LAT pathology suffers from a progressive combination of immune deficiency and severe autoimmune disease, as a result of the T immune cells not being activated properly.

The mutation was identified through the examination of the clinical and laboratory data of three Israeli Arab siblings from a consanguineous marriage (where the parents are relatives). All three patients suffered from recurrent infection caused by immune system deficiency, proliferation of lymph modes, and life-threatening autoimmune disease since early infancy. The first sibling was seen at age five months; the second, at six months; and the third, at ten months.

At five months, the male infant already exhibited severe anemia and lymph node and spleen abnormalities. At the age of seven, his spleen was removed. At age nine, it was deemed necessary to give him a stem cell transplant, but he passed away due to a severe infection with lung complications before he could have the transplant.

The second sibling, seen first at half a year, exhibited cerebral palsy and an abnormality in his brain, thanks to severe infection. From age one onward, he began contracting recurrent respiratory tract infections which progressed to chronic lung disease. He, too, suffered from an abnormal spleen and lymph nodes, along with other health problems. From the age of six, he was treated with steroids for severe Evans syndrome, an immune system malfunction, where the immune system destroys its own blood cells. At age seven, various infections caused the deterioration of his respiratory system. He was given antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy and improved gradually. At age eight, he received a stem cell transplant at Hadassah from his fully matched sibling and is doing well. The boy had been treated and followed at Rappaport Children’s Hospital and the treating physician, Dr. Irina Zaidman, head of the Pediatric Bone Marrow Transplant Unit there, initiated the collaboration with Hadassah when he was the single child still alive from the affected siblings.

When the third sibling, the younger sister, was seen at age 10 months, she exhibited gastroenteritis, recurrent pneumonia, and urinary tract infection. At age two, she died of anemia and thrombocytopenia (a deficiency of platelets in her blood).

As the authors explain, “All patients suffered from early onset autoimmune manifestations with normal lymphocyte counts and Ig levels. During the progression of the disease, the immune systems of the two older patients seemed to collapse, lymphocytopenia (abnormally low lymphocyte count) and hypogammaglobulinemia (primary immune deficiency) developed, and opportunistic as well as other infections occurred. The early death of patient three at two years of age probably explains why she did not enter the second phase of the disease observed in her siblings.”

Extensive biochemical and genetic analysis led the researchers to their finding that a disruption in the LAT signaling hub is the culprit.

“This is an additional example of successful collaboration among physicians (who are also friends), where we demonstrated how a precise genetic and immunological diagnosis can save the life of affected children. Our discovery can also help in the future, not only to identify additional patients, but also to understand the human immune system better.”

The study is highlighted in the May 30, 2016 issue of Journal of Experimental Medicine.