Translated from the Hebrew article by Yael Freund Avraham, which appeared in the Israeli newspaper Mekor Rishon.

She was walking the grounds of an Israeli college when she collapsed. At 24, she was dead. Weeks later, her paternal first cousin, aged 13, died during the night.

With two closely related tragedies, Hadassah Medical Center geneticists and physicians joined forces to establish the cause. Using the latest technology, they discovered a genetic mutation that is responsible for a fatal aortic rupture.

Once it was clear there was a life-threatening mutation in the family, senior genetic counselor and head of the Hadassah Center for Cardiogenetics Smadar Horowitz-Cederboim took to pen and paper to plot the family tree. As she built the tree, she moved from a small sheet of paper to one that covered her desk.

The father of the deceased woman has six siblings, and they have many cousins. Horowitz-Cederboim identified each man on the chart with a square and every woman with a circle. Everyone she circled was invited to her office over the next few weeks. Almost all agreed to attend and give a blood sample for genetic analysis.

“Because we know the mutation exists in this family, we can prevent the spread of the disease among the carriers and save lives,” says Horowitz-Cederboim.

As a result of the testing, the Hadassah team asked the deceased woman’s sister to make some life-saving changes to her health regimen. Her sister is completing high school and was planning on full service in the Israel Defense Forces, coupled with continuing her outstanding athletic career.

However, the Center for Cardiogenetics team told her she could not serve as a regular soldier and must reduce her athletic activities.

Horowitz-Cederboim explained to her, “This isn’t the worst day of your life. It is the best. I’m not telling you that you’re sick, but that together, we can take steps to prevent you from getting the disease. If I were to tell you that a ladder will fall and kill you, you wouldn’t walk under it.”

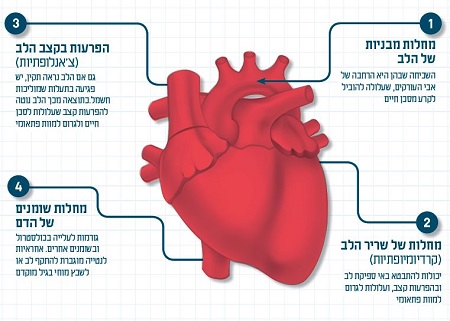

Cardiologist Dr. Ronen Durst adds, “There’s a psychological impact when you relate the news, but cardiology is actually a very optimistic discipline. In nearly all types of heart disease, we can offer a solution. It can be anything from lifestyle changes to routine checkups, catheterization, or surgery.”

One of the main functions of the center’s staff is to explain the implications in easy-to-understand language. It is then up to the patients to decide what to do with that knowledge— to keep it private or share it with their children. Just because one is a carrier does not mean that the carrier will contract heart disease.

“Sometimes you hear family members ask, ‘You knew there was a chance I’d get sick and you didn’t say anything,’?” says Horowitz-Cederboim.

In most cases, the medical team has to deal with the parents’ feelings of guilt. Dr. Durst explains, “It’s particularly prevalent in our culture. In some Israeli sectors, details of genetic problems are hidden when a family member is about to marry. These are some of the issues we deal with and have to do so sympathetically.”

Genetic testing for heart conditions had been a little behind the curve. A lot more attention was placed on cancer genetics over the last 20 years. However, with the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS), things have changed.

“The new technologies have made genetic testing more commonplace, more thorough, and far cheaper,” says Horowitz-Cederboim. “Not too long ago, tests cost thousands of shekels. So you could perhaps test two genes, but the mutation was actually in a third gene that you chose not to test because there was no more money for testing.”

Another issue that hampered advances was that doctors didn’t always treat heart disease as potentially genetic.

It was after Dr. Durst spent a couple of years at Harvard University a decade ago that NGS began to take off. This shift from testing individual genes to mass sequencing “opened a whole new clinical world,” he says. “It meant cardiology became more accurate, not only in isolating carriers in a family but also in determining appropriate treatments.”

Prof. Ofer Amir, the new director of Hadassah’s Irma and Paul Milstein Heart Center, describes the bigger picture: “From our daily clinical work, we learn a great deal about the local population. Jews and Muslims aren’t sufficiently represented in the international medical literature. Comprehensive genome testing of the broad Israeli population and its subgroups means we can identify typical hereditary risk factors. We can, therefore, deepen our understanding and improve treatment for patients and their families.”

Read the Hebrew version of this article in Mekor Rishon.